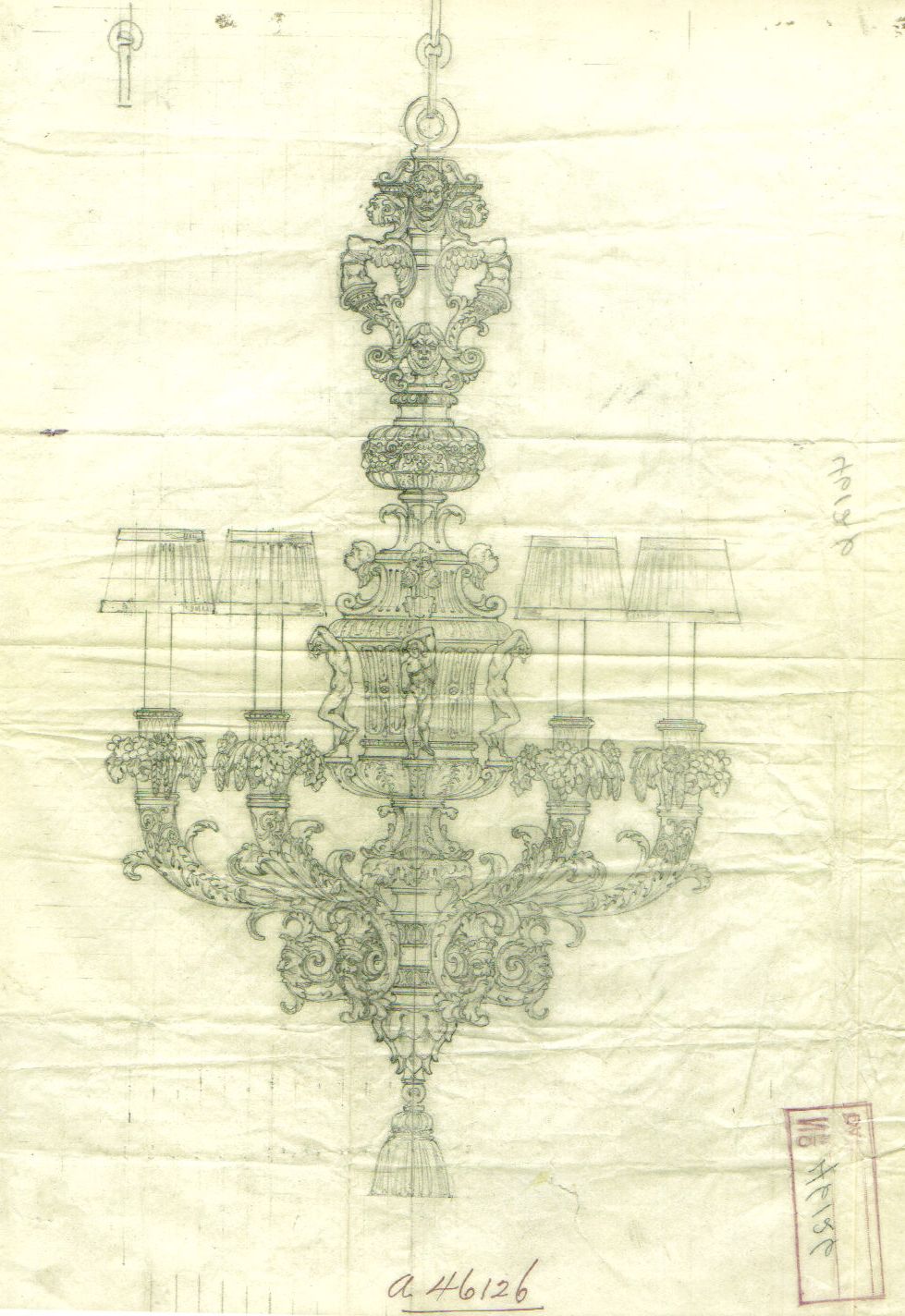

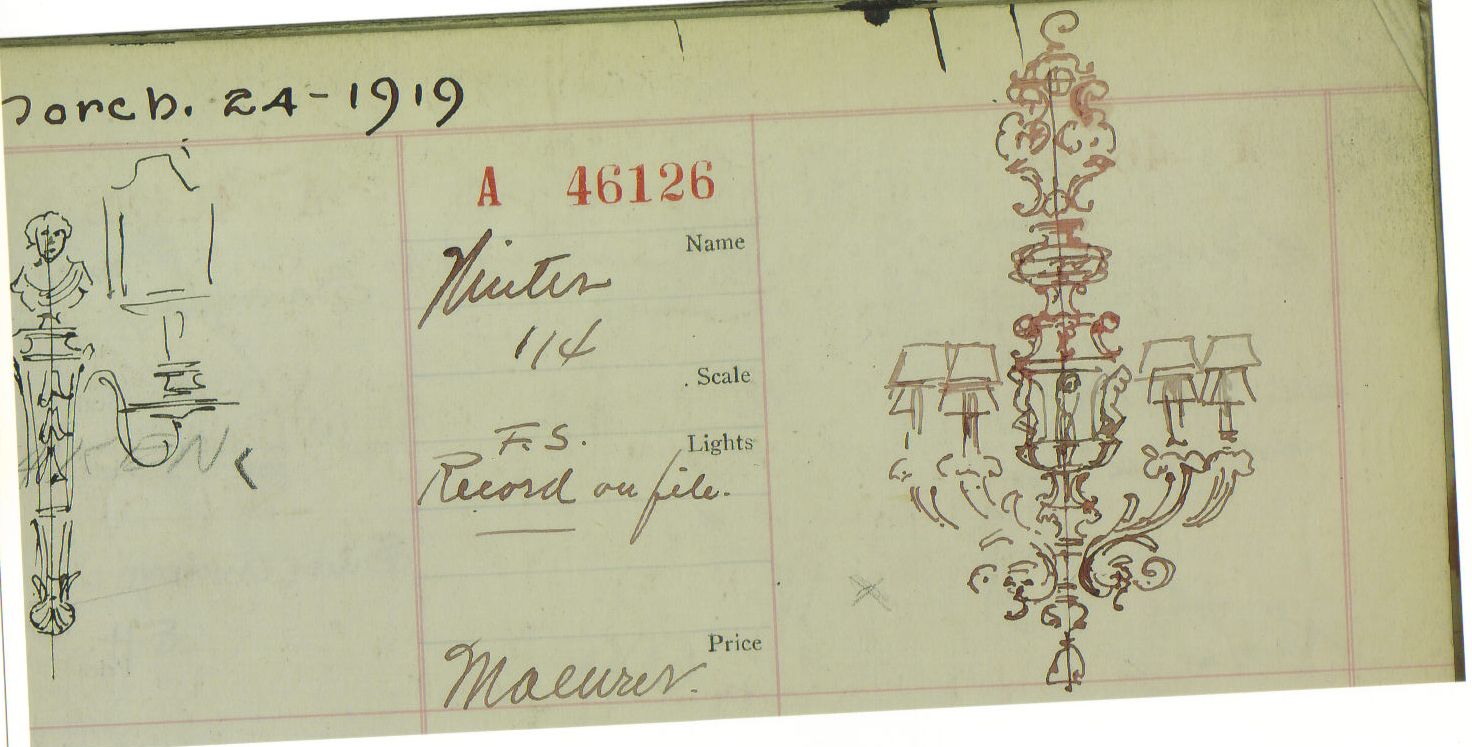

The chandelier with a pierced corona cast with grotesque masks and griffin herms, above a campana-form body decorated overall with foliage, rocaille and further masks, surrounded by three Atlas figures, the foot cast with dolphins, issuing six cornucopia-form arms, each overflowing with a bounty of fruit above a Zephyr mask.

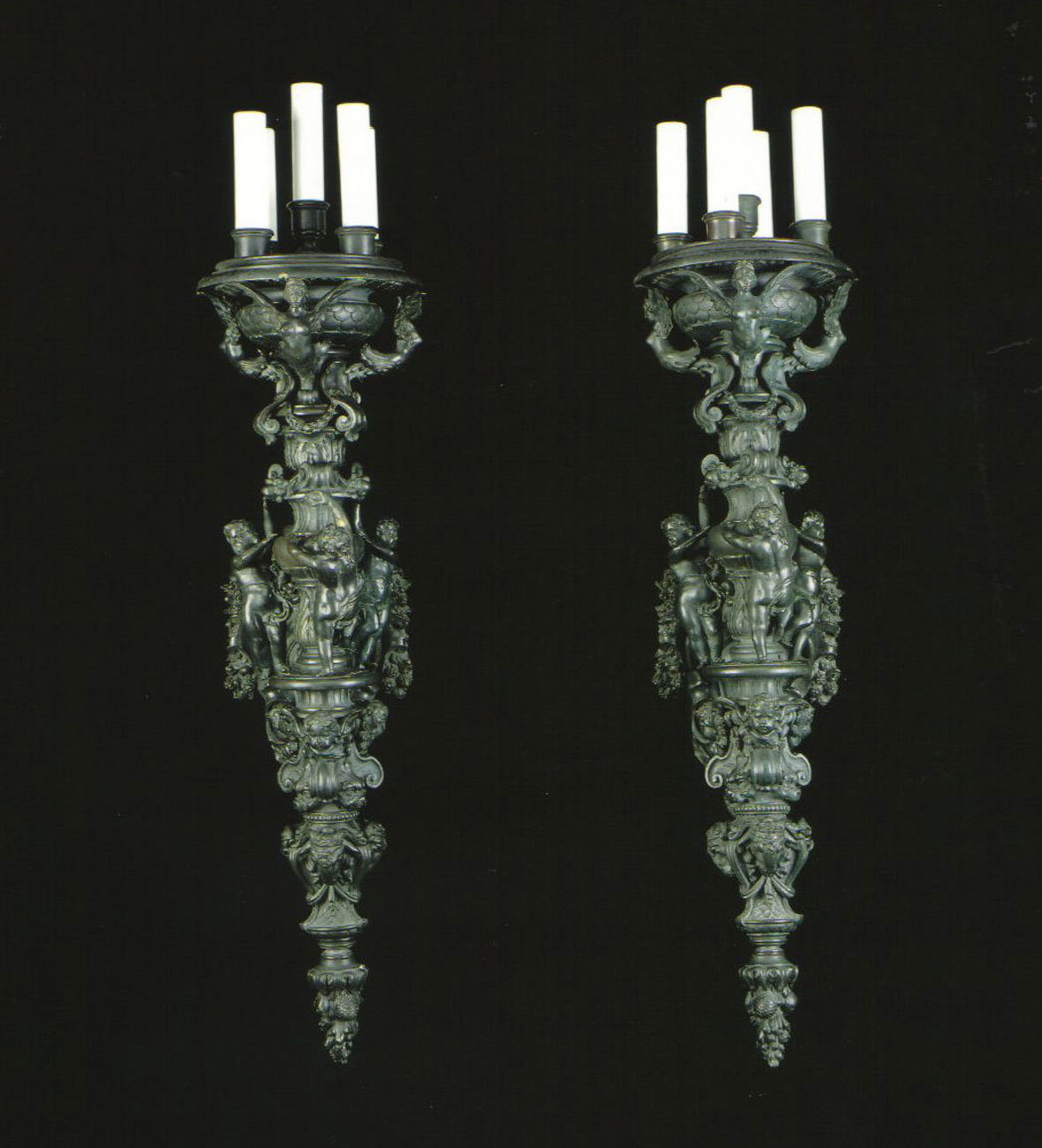

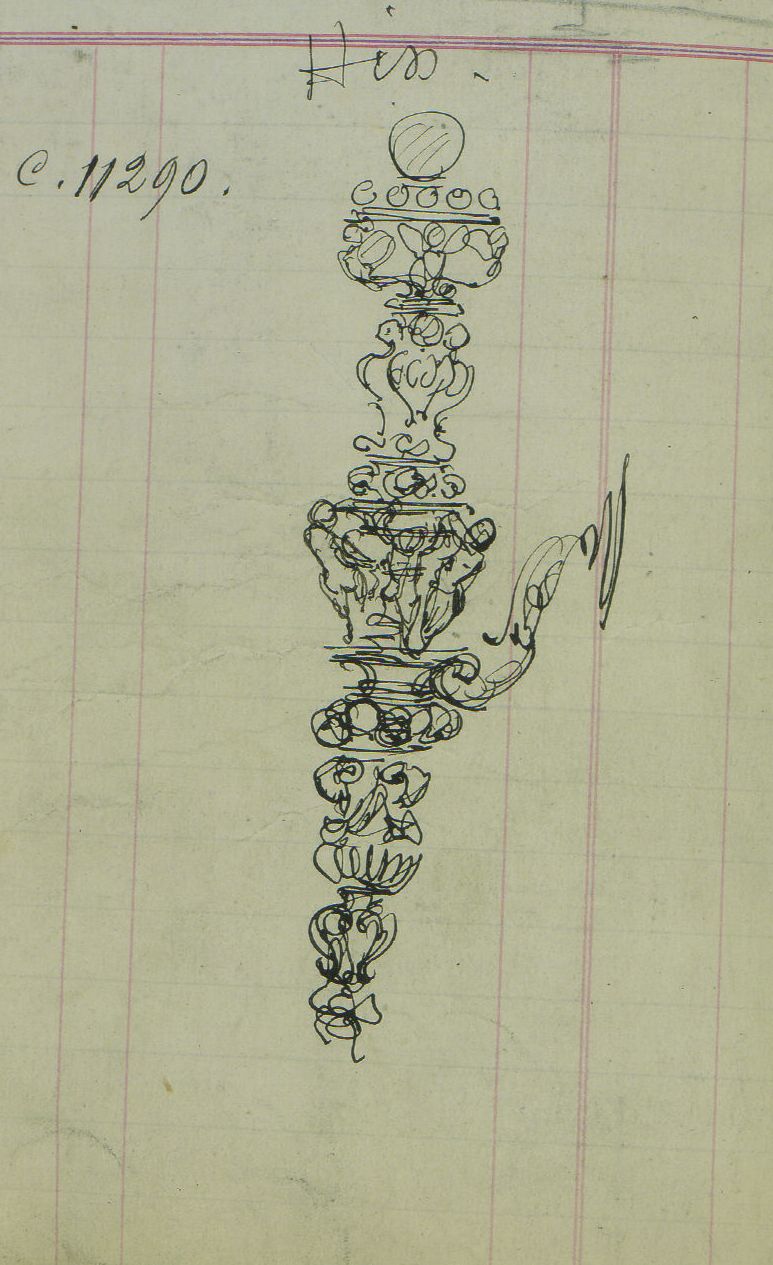

Each wall appliqué with circular top supporting four nozzles and a central raised nozzle, above an urn with baluster stem intricately modelled with winged females, putti, cherubs, rams' masks, swags and cartouches, terminating in a fruiting finial, the cartouche-form backplate with shell surmount

Chandelier: 45 in (114.3 cm) long

Each Wall Appliqué: 37 in (94 cm) high

Provenance

Emil Winter

cf. J.L. Sandberg, 'Edward F. Caldwell', The Antiques Magazine, February 1998

Although the Thaw family amassed a fortune through railroads and canals, the estate itself is perhaps best-known as the boyhood home of William's son, Harry Kendall Thaw (d. 1947). Harry Thaw became infamous during his sensationalized trial for the 1906 murder of architect Stanford White on the roof of Madison Square Garden in New York. The 'Crime of the Century' was instigated by rivalry for the beautiful redhead Evelyn Nesbit, better known as 'The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing'.

Edward Caldwell's affiliation with his friend Stanford White, partner in the firm of McKim, Mead, and White, ensured Caldwell's work appeared in the most prominent commissions, including the homes of Andrew Carnegie and Frederick W. Vanderbilt, and the Taft White House.

Draughtsman's sketches of the chandelier and this pair of wall appliqués are held in the Caldwell Archives in the New York Public Library. They were recorded in the company's ledger in 1919, and it was around that date that they were added to Lyndhurst during renovations after Winter's purchase of the mansion. There is a period photograph which shows the chandelier in situ at Lyndhurst. Winter spared no expense, decorating with the highest quality pieces. For example, the archives of François Linke, leading cabinetmaker of the Belle Epoque, indicate that between 1912 and 1925 Winter ordered no less than 17 items from the atelier (see Christopher Payne, François Linke, 1855-1946, The Belle Epoque of French Furniture, Woodbridge, 2003, p. 252). After his death, Winter's heirs sold the majority of the contents of Lyndhurst at Parke-Bernet, 15-17 January 1942. Trinity Court Studio published a folio book which illustrated the house and its interior.

Edward F. Caldwell and Company

The New York firm established in 1895 by Edward F. Caldwell was perhaps the leading American designer of lighting fixtures and decorative objects during the first quarter of the 20th century. Working from its foundry at 38 West 15th Street, the company supplied fine quality products to wealthy and distinguished clients including Andrew Carnegie, Henry Clay Frick, J. Pierpont Morgan and Frederick W. Vanderbilt. Caldwell also received important public commissions including that for lighting fixtures for the White House in Washington, DC.

The company's rich and conservative clientele preferred traditional interiors, so Caldwell based his lighting fixtures predominantly on historical styles, often using photographs of objects in European palaces as models, or relying on 18th-century pattern books. Caldwell himself made frequent trips to Europe to study the best of French, English and Italian craftsmanship. The company provided exact copies of antiques and could also create new designs based on them.

The Caldwell Company's work most often stemmed from an architectural commission in which lighting was considered an integral element of the design. With architects, interior decorators and many subcontractors working together on a project, the different parties depended heavily upon the compendiums of drawings and photographs that are now part of the Edward F. Caldwell and Company collection at the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum in New York City. When the architect requested fixtures of a certain period or character, Caldwell either provided samples of the company's work or, more often, photographs of past designs that could be altered to suit the commission. A sketch of a new design would be made, followed by scaled working and presentation drawings, and finally, if needed, blueprints to help in the production of the piece.

Caldwell's work was critical to an interior design scheme because there were few products on the market specifically for electric lighting that would not be obtrusive in a room full of antiques. For example, while it would be difficult to find eight matching 18th-century wall brackets as specified by an architect, Caldwell's fixtures could be made in multiples and designed to correspond exactly to the other decorative elements in the room.

Residential work predominated during the firm's first decade mainly because of the large number of houses built by wealthy financiers around 1900. One of the company's earliest documented commissions was the Frederick W. Vanderbilt house in Hyde Park, New York, designed by McKim, Mead and White and built between 1895 and 1899. The house was lavishly decorated by the most noted firms in New York City including Caldwell, whose wall brackets (depicting satyrs and cornucopias) were installed in the major rooms.

During a time of rapidly changing notions about machine production in the decorative arts, Caldwell and Company maintained its commitment to handcraftsmanship. The company participated in the first exhibition of the Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, in 1897 and the American Federation of the Arts exhibition of metalwork and textiles at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City in 1930. Both Edward Caldwell and his firm were highly respected in the design community and won many honours and awards. He achieved great success in creating fixtures for the New York State Building at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Caldwell was made a Fellow of the American Academy in Rome in 1905 and the company survived the Great Depression by winning contracts for large public buildings, including several government buildings in Washington, DC, as well as some of the lighting at Colonial Williamsburg in Williamsburg, Virginia.